Two goddesses and a child carved in ivory, c. 1400-1200 BC. Many such triads exist from Sumeria to Classical Greece

Two goddesses and a child carved in ivory, c. 1400-1200 BC. Many such triads exist from Sumeria to Classical Greece

“I dream of a place between your breasts

to build my house like a haven

where I plant my crops

in your body

an endless harvest

where the commonest rock

is moonstone and ebony opal

giving milk to all my hungers

and your night comes down upon me

like a nurturing rain.”

– Audre Lorde[i]

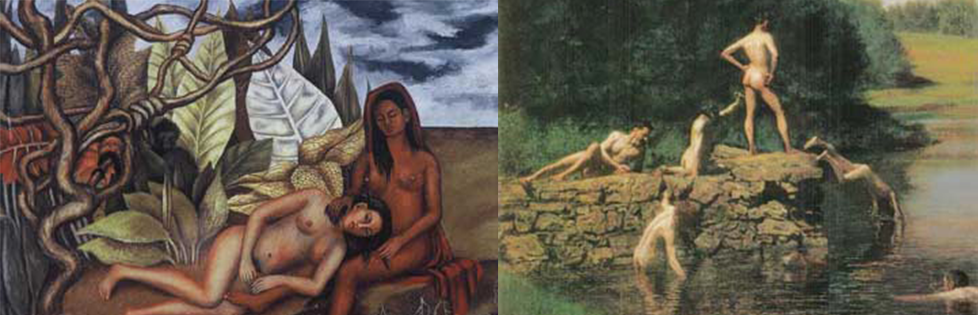

The Mother and the Maid appear as a dyad over and over in the myths and stories of the West. Sometimes they are one woman, like the Virgin / Mother of Christianity. Sometimes they are a lesbian couple, like the Two Goddesses at the most famous sanctuary in ancient Greece, Eleusis: Demeter and Kore; Earth Mother and Maid.

The story goes like this: the two inseparable goddesses are split apart when the Virgin Kore is abducted by Hades, Lord of the Dead. Demeter grieves inconsolably. She rages so violently that every seed is prevented from sprouting. The earth is barren, parched and withered. Finally Hades is convinced to release the ravished Kore, so that the Earth can bloom again. At the last moment, Kore eats a pomegranate seed that Hades offers. Contaminated, she must return again every winter to spend part of the year in the land of the Dead. Every winter, Demeter grieves; the earth shrivels and dies. When the Maid returns to the Mother each spring, the whole world rejoices.

The Mother, Demeter, is Kore’s mother. And she is Kore’s lover. Scholar Walter F. Otto compares the relations of other daughters of Greek myths to their divine parents, and finds none so intimate. Carl Kerényi comments, “The fervor of their love for one another reminds us rather of divine lovers such as Aphrodite and Adonis. . . .”[ii] If we accept that the Mother and the Maid read as lovers, we find the key to Demeter’s wild grief, and Kore’s withholding. The two women are bound together as closely as lovers, and separated as painfully. Reunited, they fall on each other with passionate kisses.

Every lesbian relationship engages the archetype of the Maid and the Mother. This is not to say that there ever is a lesbian relationship where one partner plays the mother and the other partner plays at being mothered. But as usual, this stereotype opens into something more interesting. The turn to a woman’s body is often experienced by lesbians with a sense of homecoming. Between our lover’s thighs, we come home to the Mother’s body. Inside her, we find a place that held us before we were born. Here we can at last become the daughters we are and give birth to.

Vulva carved into rock face inside a cave, c. 30,000 BC, France

Vulva carved into rock face inside a cave, c. 30,000 BC, France

Patriarchal culture separates mothers from daughters. It keeps women apart from one another. The social and symbolic order precludes each woman’s joy, imprisons her capacities, and excises her sex. Loving lesbians, we come home to our own bodies. Reaching out to her, we touch ourselves. In the words and gestures that love invents between us, we redeem the Mother who had no power to teach us. When the Mother is delivered from her patriarchal imprisonment, we can inhabit our own bodies for the first time.

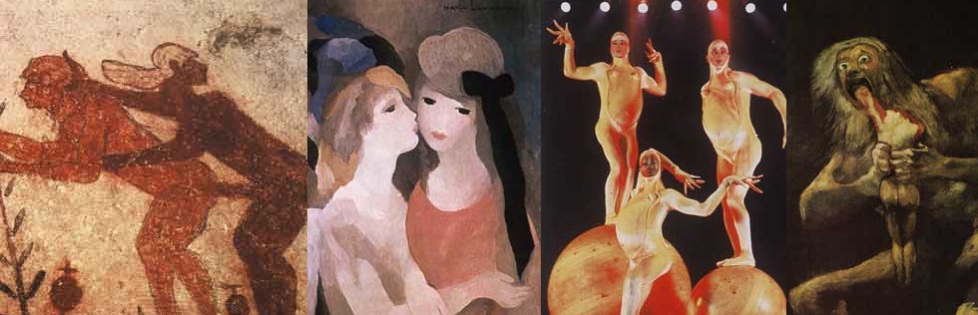

The story of the Maid and the Mother represents same-sex love as an initiation to the wild order of life and death, the deepest of Earth’s mysteries. Carl Jung describes the mother archetype: “mother love…is… the mysterious root of all growth and change; the love that means homecoming, shelter, and the long silence from which everything begins and in which everything ends. Intimately known and strange like Nature, lovingly tender and yet cruel like fate, joyous and untiring giver of life – mater dolorosa and mute implacable portal that closes upon the dead.”[iii] Demeter is Earth Mother, origin and end. It is she who speaks for (initiates) the cycle of death and rebirth in which every life is enmeshed. And it is she who grieves inconsolably, raging, refusing ever to accept or understand the loss of her beloved to Death.

Carl Kerényi interprets Kore as representing “that which constitutes the structure of the living creature apart from this endlessly repeated drama [symbolized by Demeter] of coming-to-be and passing-away, namely the uniqueness of the individual and its enthrallment to non-being.” [iv]That which is unique in us will die. It is our individuality which differentiates us each from the continuum of being and links us with non-being and death. Kore’s story invokes our inevitable fate. But where the Mother grieves and rages, the Maid surrenders. Kore accepts the initiation and moves to live inside the mystery: death in life, life in death.

We cannot have life without death, but only a shriveled semblance of life, parched by withholding. We cannot love without loss. There is no inconsolable heartbreak without unspeakable gladness. So much of contemporary society seems intent upon avoiding risk. Old age is approached as a disease to cure. Science intends to conquer disability. Children are confined to playpens. Love appears only as weak sentiment. We need the Maid and the Mother to guide us to the mystery, or we will stay stuck on the surface, clinging to youth, picking flowers, avoiding the dark chasm where we meet loss, and grief, and mortal destiny.

Lesbian love brings us home to the Mother we never had. Through our lovers we find our source and our surcease. We experience enmeshment with one another and with the continuum of all life. And yet lesbian love challenges us to differentiation. We are enjoined in battle against the patriarchy, wounded, denied, called to use every ounce of our power. Our lovers cherish our strengths. They summon us to our capacities. They admire our songs. As personal voice and individuality grows stronger, the threat and risk of loss is greater. Our passions lead us to the maw of fear. If we dare to move inside, we face the season of despair. And we come, again and again, to Spring.

Through union with the Mother we experience the unity of life. Through identity with the Maid, we come to know our uniqueness, solitude and strength. Patriarchal socialization requires each of us to disavow the Mother and break irrevocably with the unity of self and world we know in her body.[v] Individuality is valued and commonality is denied. The end of life is as feared as the beginning. The Maid and the Mother invite us to a different way of being in the world, extending and transforming the empathic continuum of life with each person’s individuality and differentiation.

The mystery accepts that, always, some part of world or self is lost and broken. We can admit grief, without being paralyzed by fear of grief. We can go down beneath the surface and live with our own deepest fears, until love bids us back to a beginning. When we meet her again, the sun is shining. Birds sing. Flowers begin to open. The air smells of fresh spring rain. Our joy in each other’s arms is boundless. Our love goes deep enough to call the world to life.

[i] Audre Lorde, 1978, (82).

[ii] Carl G. Jung and Carl Kerényi, 1949, (179).

[iii] Carl Jung, 1959, (428).

[iv] ibid. (123).

[v] Catherine Keller asks, “What would it be like if the original continuum from which we all emerge . . . [was] neither shattered nor repressed, but extended and transformed?” Quoted by Karin Lofthus Carrington, in Robert H. Hopke, Karen Loftus Carrington and Scott Wirth. (Eds.), 1993, (90). This chapter owes much to Carrington’s analysis.