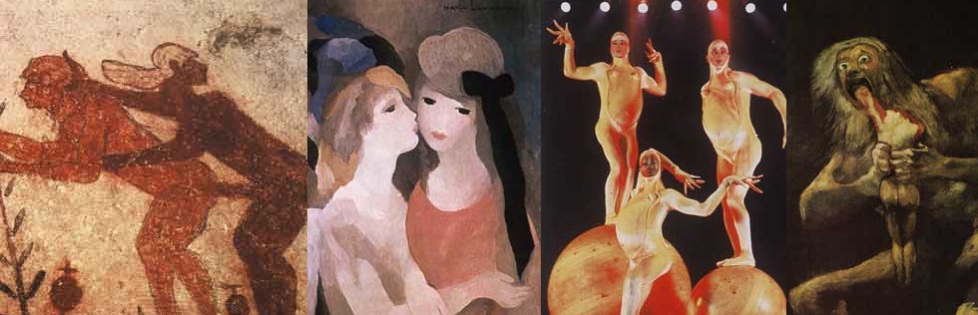

Goya, Saturn Devouring One of His Sons. 1820-23. Oil on plaster transferred to canvas. 57-1/2” x 32-3/4”. (146 x 83 cm.). Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Goya, Saturn Devouring One of His Sons. 1820-23. Oil on plaster transferred to canvas. 57-1/2” x 32-3/4”. (146 x 83 cm.). Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

The first hint of same-sex sexuality in the Holy Bible appears in Genesis 9. Ham is in his tent with his father Noah when the patriarch is stark naked and dead drunk. Ham goes and tells his brothers, who take a coat and, walking backwards into the tent, cover Noah. The good brothers keep their faces averted to avoid the terrible sin of the same-sex gaze.[i] Ham – who dared to speak of his father’s nakedness, perhaps even to laugh at the drunk old man – is condemned to be a servant of servants, father of slaves.

The humorless god who orchestrates this absurd crime and ghastly punishment is, as James Baldwin comments, “a profound and dangerous failure of concept.”[ii] This is the same god who tells Noah, “And the fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth, and upon every fowl of the air, upon all that moveth upon the earth, and upon all the fishes of the sea; into your hand are they delivered” (Genesis 9: 2). Subjugating nature, prohibiting and punishing the same-sex gaze, demanding obsequious compliance with the patriarchal order, encouraging every grotesque exploitation of stigmatized others: these strands are braided together to make a god as mean and small as they come.

The sky god of Judeo-Christian tradition hates and punishes homosexuality. Colin Spence notes that in the early days of the formation of the Hebrew nation, the Jewish people “were surrounded by cultures which celebrated male temple prostitution.”[iii] Hebraic injunctions against sodomy are injunctions against these eunuch priests and their magical powers. Christianity revived the notion of eunuch priests, and the Christian church wove many homoerotic images and archetypes into its iconography. But Christianity maintained and refined the Hebraic prohibition against sodomy. The humorless and punishing sky god met the needs of patriarchy and imperialism. The prohibition on sodomy kept relations between men under control – no rapture that might rupture the holy offices of trade and inheritance.

Michelangelo, Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel ceiling

White Western Man is drained of blood and sex, earth and laughter. These are left to others and objects: women, “Negroes”, natives, mother earth. The sky god represses the chthonic deities and strips homoeroticism of its power. It is a culture of denial – what Luce Irigaray calls “the sovereign authority of pretense which does not yet recognize its endogamies.”[vi] Goods are traded and power circulates between white men, passing from father to son – but these patriarchal relationships are purely symbolic, not erotic. There can be no pleasure without possession. False innocence is preserved by deadly violence.

Ham’s brothers look the other way, and walk backwards into the tent to cover Noah’s nakedness. They thereby claim a patrimony that includes the right to enslave their brother’s children. Ham is a Trickster figure, the Divine Fool who laughs at the Patriarch. He tells the truth; he dares the transgression; he is alive to the possibility of sex between men and between fathers and sons. Ham’s brothers will not see and cannot admit the Father’s silliness or his sexuality. For them the patriarchal authority is inevitable and impenetrable. They claim a just reward for willful blindness. The sky god rewards false innocence. His subjects are preserved from inadmissible knowledge of world and self. The boundaries between Good and Evil are clear and smooth. They are policed with blame, shame and brutal violence.

The construction of race and sexuality are entwined in the story of Ham. James Baldwin suggests that the construction of the Negro and the homosexual both begin with a concept of god that “is not big enough.” He writes, “To be with God is really to be involved with some enormous, overwhelming desire, and joy, and power which you cannot control, which controls you . . . . I conceive of God . . . as a means of liberation and not a means to control others.”[v] Being queer, we are called to enter a gigantic imagination of god. Instead of claiming a concept of god small enough to be agreed upon, we can admit to not knowing. Not knowing is humility, emptiness, readiness. Not knowing is an open mind and a heart that can admit what is new, transforming, impossible.[vi] If we don’t know or understand what god is, we might prefer acceptance and love to righteousness and punishment.

To accept the horror of history, and still believe we can weave a future loving nature, honoring women, embracing homosexuality and dismantling whiteness, we need a faith past all understanding. Yet divine is there, in a sunlit moment, in the eyes of a stranger, in the arms of a lover. Despite the parsimony of the sky-god’s self-appointed spokespeople, the world in all its wonder does persist.

Divine is also a verb. Being queer means walking through the world divining, with intuitive recognitions and prophetic insights. Despite the absence and denial that confronts us everywhere, we divine the love that creates us as queer people. Passion, engagement, sweet astonishment, blinding certainty – this love is an overwhelming, unpredictable power that can only be god.

[i] Sander Gilman describes Ham as guilty of the “most heinous of all sexual acts, the same-sex gaze.” In fact the “most heinous” act is surely not the gaze itself, but the father-son incest which is implied. See S.L. Gilman, 1989, Sexuality.

[ii] James Baldwin, 1949, (42).

[iii] Colin Spence, 1995, (56).

[vi] Luce Irigaray, “When the Goods Get Together,” in Elaine Marks and Isabella de Courtivron, eds., (107), emphasis original.

[v] James Baldwin, 1985, (234); see also 1949.

[vi] Peter London, 1989, (80) discusses not knowing as a key to creativity.