One of the Nommo, androgynous ancestors of the Dogon people of West Africa

One of the Nommo, androgynous ancestors of the Dogon people of West Africa

The Dogon of Africa believe that every child is born with both a male and a female soul. At puberty, one soul is chosen and the other is cut away with cliterodectomy or circumcision. Without this violent excision, no one would develop the inclination for procreation.

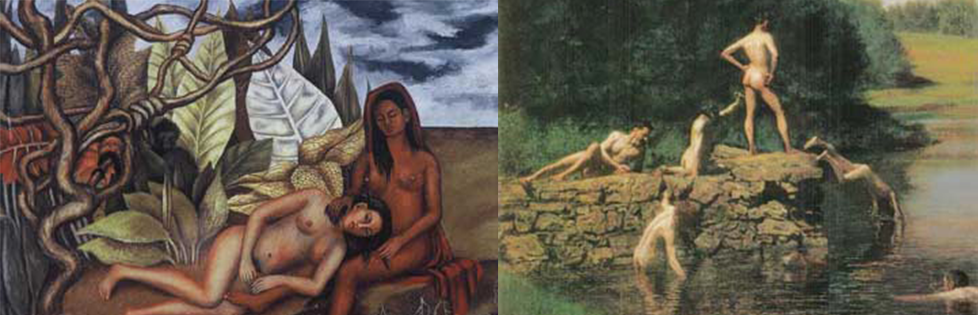

The Androgyne is a symbol of wholeness, an original innocence from which we are wrenched away by the requirements of gender, culture and maturity. In Western culture, at least, learning the requirements of sexuality is equivalent to the paring away of capacities. Boys forgo sensitivity, receptivity and inwardness to assume the perks of manhood. Girls learn to denigrate and fear their power and independence to become acceptable women. These psychic excisions are violent and painful mutilations. Often the wounds refuse to heal.

Queers are called away from the carnage, back to the carefree joys of an ideal childhood. Like Peter Pan, we say “I won’t grow up,” and it gives us wings. We refuse the weight and obligations of so-called maturity. With irritating acumen, people keep calling us “boys” and “girls” no matter how old we become. So long as we avoid the tasks and wounds of adult male and female sexual identities, we are identified with the archetype of innocence.

William van Gloeden, Untitled photograph, c. 1900

William van Gloeden, Untitled photograph, c. 1900

Mark Thompson writes, “I would define gay people as possessing a luminous quality of being, a differentness that accentuates the gifts of compassion, empathy, healing, interpretation and enabling. I see gay people as in-between-ones; uniting opposing forces as one.” Ostensibly opposing forces organize thought as they organize life. Masculine / feminine is one such duality. Bound together like a pair of mules headed in opposite directions, male / female is going nowhere and getting exhausted. Queer people slip between binaries, building bridges or creating strategies of resistance. Thompson continues, “For me, gay people represent the archetype of innocence, a shaman’s tool that allows access to a more primal world, one where his / her work is done.”[i] With this notion of innocence as a “shaman’s tool,” Thompson suggests a way through another ostensible opposition – that between initiation and innocence. Queer innocence is not constituted in denial, withholding, and fear of life experience. It is a way of meeting inner and outer worlds with optimism and trust – opening like a flower, bending towards the light, responding to the inner impulse.

At the movies, on the street, in the news, and in the popular imagination, homosexuality is linked with crime and violence. Priests rape altar boys. A lesbian becomes a serial killer. In Littleton, Colorado, young boys called “faggots” murder fourteen classmates, then themselves. These characters may have nothing to do with the great adventure of being gay, but they have much to do with the presence of homosexuality in the general culture. Occasionally homosexuality is not so obviously an aspect of the crime or the criminal, but it is always an aspect of the punishment. Every cop show, news report, and sociological study restates the threat, usually without quite saying the words – no one gets out of prison without some kind of (unwanted) homosexual experience.

We may be tempted to counter all this association of homosexuality with crime and violence by self-righteously proclaiming our innocence. Donning a public mask of wide-eyed innocence is nothing like using innocence as a “shaman’s tool.” As a mask and a posture, innocence invites wounding and mortification. We talk about the effeminate boy, born gay, bullied into suicide. We talk about the lesbian mother, who realizes her true self, only to lose custody of her beloved children. Innocence segues into pain and loss, inviting pity, beseeching forgiveness. If we are guilty of being gay, it’s not our fault. Blame genetics, blame mom and dad, blame the society that oppresses us. They can accept us – or perhaps more to the point, we can accept ourselves, when we are innocent and therefore victims.

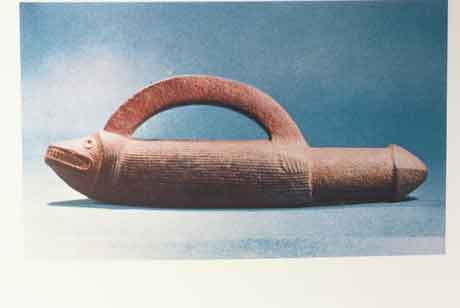

Pacific Northwest Coast double phallus, 13”, believed to be used in initiation ceremonies

Embracing the adventure of homosexuality, we can lift this mask of innocence. Cruelty, aggression, promiscuity and violence can surely be acknowledged without subsuming our souls. Depravity claims space. It can occupy us as the polar opposite of false innocence, expressed in pathologies and exorcised with self-righteousness. Or depravity can find subtle expressions and finally-articulated niches, in costume, erotic play, art, philosophy, sexual cultures. “The inner world is a place of blood and fire, tears and mud,” Mark Thompson writes elsewhere.[ii] Our worst nightmares lead us deep inside. Given time and attention, they feed culture and nourish the soul.

We include both wide-eyed innocence and genuine depravity. Accepting this, we can use innocence as a “shaman’s tool,” instead of a brittle mask. We can honor the polymorphous perversity that curiously belongs to the deepest innocence. Deepening our innocence with initiation, we learn to invite pleasure over mortification. Purity of heart, playfulness, trust and openness are pathways to defilement, self-acceptance, and integration of the Shadow.

Eros is a child like this: androgynous, pre-pubescent, mischievous. The mingling of Eros and Chaos begins the world. Certainly, Eros and Chaos create us. Often with surprising reversals and a chaotic re-ordering of values and expectations, love invents queer lives. We are perverted by desire – turned around and connected with a primal order, a cosmogonic energy.

Our love for one another can be profoundly innocent – playful, open-hearted, trusting. It can be limitless, passionate, and chaotic. In one another’s arms, we hold an awful mystery, a terrible pain, an incomprehensible depravity. And we hold on. Following the innocent heart of desire, we learn to love each other whole.

[i] Mark Thompson, 1987, (xvi).

[ii] Mark Thompson, ed., 1991, (xviii).