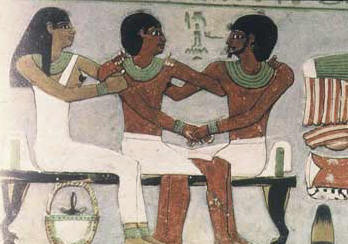

Two men and a woman at table, attended by a servant girl. Funeral stele c. 2100 BC.

Two men and a woman at table, attended by a servant girl. Funeral stele c. 2100 BC.

The homophobes always claim, “homosexuality undermines the family.” But nothing is harder on the family than heterosexuality, at least as it is engaged within the tiny parameters of the single family dwelling. Driven by the legal fiction of paternity, or the requirements of capitalism for free wage labour, modern life tends to separate heterosexual couples and their offspring from large communities and extended families. The post-war dream of suburban living takes people even farther from friends and kin. Inside the house in the suburbs, central heating, convenience food, and gender-marked spaces further separate men, women and children from each other. Older patterns of communal living disappear.[i]

The phrase “nuclear family” comes into the language in 1947, two years after the first nuclear bombs were detonated. The metaphor describes the situation pretty well: families structured like atoms, discrete entities, with a father and mother at the nucleus, and children who revolve around them. Add to this the fact that science and society have managed to split the atomic nucleus, creating a violent explosion from the chain reaction, fission leading to further fission. Inside this unstable and dangerous construct, who would not be lonely, angry and afraid?

Homosexuals escape this fate. We are the women who can say to their mothers, with Audre Lorde:

But I have peeled away your anger

down to the core of love

and look mother

I am

a dark temple where your true spirit rises

beautiful

and tough as chestnut[ii]

We are the men who, as in Ranier Maria Rilke’s poem, stand up during supper and walk outdoors, while “another man, who remains inside/ his own house,/ dies there, inside the dishes and the glasses. . . .”[iii] In each queer person there is a true spirit that cannot shine in the dead forms and obligatory gestures of nuclear family life. We peel away the anger, down to the core of love. It gives us a different chance at living.

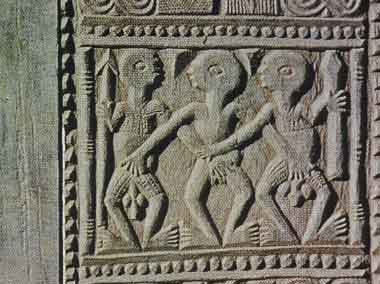

Carved Door, detail, from Modakele, Ife, Africa

Carved Door, detail, from Modakele, Ife, Africa

Being queer means we do not let mother and father alone create us. We are nurtured by the world, taught to live by one another. As children we look outside the family for mentors and teachers who can show us other ways of living. Our kinship is not just with the family tree of heterosexual pairings, even including the odd spinster aunt and bachelor uncle whose branch is truncated. Our ancestors include real trees – madrone, oak – and flowers: pansy, narcissus, hyacinth. We claim kinship with salmon swimming upstream, transgendered grizzly bears that copulate and give birth through their penises, homosexual male black swans and their beloved offspring, lesbian spinner dolphins who fuck each other while they swim.[iv]We have an affinity with other societies, where nuclear families are unknown. In the words of archetypal psychologist James Hillman, “ancestors are not bound to human bodies and certainly not confined to human souls.”[v]

Female Grizzly Bears sometimes bond with each other and raise their young together as a single family unit. The two mothers become inseparable companions for a year, traveling and feeding together as they share the parenting of their cubs. Young male black bears sometimes mount their siblings, male and female. Intersexual or hermaphrodite Black and Grizzly Bears occur in some populations. These individuals are genetically female and have female internal reproductive organs, combined in various degrees with male external genitalia.[vi]

Female Grizzly Bears sometimes bond with each other and raise their young together as a single family unit. The two mothers become inseparable companions for a year, traveling and feeding together as they share the parenting of their cubs. Young male black bears sometimes mount their siblings, male and female. Intersexual or hermaphrodite Black and Grizzly Bears occur in some populations. These individuals are genetically female and have female internal reproductive organs, combined in various degrees with male external genitalia.[vi]

“Honor thy father and thy mother.” Hillman points out that “the Fifth Commandment, along with the ones preceding it, aims to eliminate all traces of pagan polytheism. . . .” For polytheism a larger view of ancestry, and our kinship with all life, is an informing vision. Queer harkens back to the idolatry of the old nature religions.

Called outside the nuclear family to find our origins, we are freed of what Hillman calls the “parental fallacy.” Mothers and fathers are not the primary instruments of our fate. We can attend to the social, environmental, and economic forces that shape us. We can leave behind infantile deprivations, without harboring the resentments that seem to stunt so many lives. Sometimes, we can even embrace people in our family of origin. It seems easier to forgive them for not being the abstract fantasy family we might have dreamed of, when we are not trying to reproduce the thing ourselves.

“We are family,” as the song goes. In queer community, we have what the homophobes promoting “family values” yearn for. While they look to constitute family by enforcing gender inequalities, promoting guilt, and compelling dependencies, the children pay. In Canada and the United States, more children and adolescents die from suicide than from cancer, AIDS, birth defects, influenza, heart disease and pneumonia combined.[vii] Modeling alternate forms of love and belonging, advocating for the rights of children, and creating alternate spaces of support for escapees from the nuclear family blast, we do undermine the family.

John D’Emilio writes, “building an ‘affectional community’ . . . . we may prefigure the shape of personal relationships in a society grounded in equality and justice rather than exploitation and oppression, a society where autonomy and security do not preclude each other, but coexist.”[viii] For the sake of young people trapped in hopeless isolation and abject dependency, the end of the nuclear family cannot come soon enough.

[i] Alexander Wilson, 1991, points this out.

[ii] Audre Lorde, 1978 (82).

[iii] Ranier Maria Rilke, Robert Bly, trans., 1981.

[iv] See Bruce Bagemihl, 1999, for these and many other examples of animal homosexuality, intersexuality, transgender and non-reproductive sexualities.

[v] James Hillman, 1996 (85-90).

[vi] Bruce Bagemihl, Biological Exuberance: Animal Homosexuality and Natural Diversity, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999

[vii] Statistics from U.S. quoted by James Hillman. Statistics Canada, “Mortality: Summary List of Causes,” 1997, calculated for ages 10 to 19, based on tables p. (10-13).

[viii] John D’Emilio, in Abelove et. al., 1993, (475).