Worms. Individual worms typically have both male and female organs. To mate they align their bodies with a partner and cross-fertilize one another simultaneously.[i]

Worms. Individual worms typically have both male and female organs. To mate they align their bodies with a partner and cross-fertilize one another simultaneously.[i]

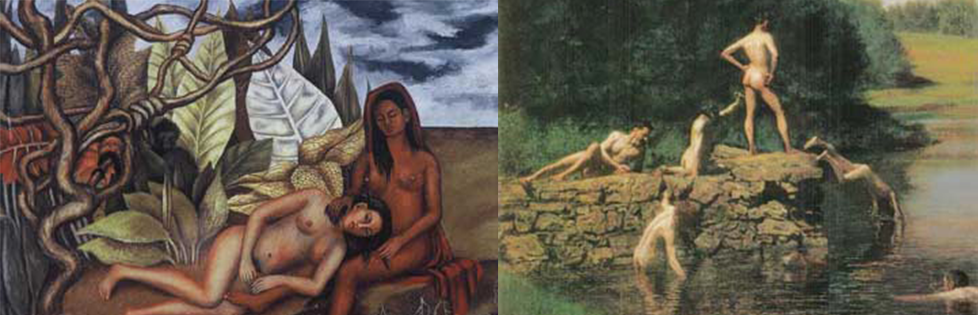

“Homosexuality is not natural,” claimed parliamentarian Roseanne Skoke in the Canadian House of Commons. “It is immoral and it is undermining the inherent rights and values of our Canadian families and it must not and should not be condoned.”[ii] With their hatred known as opinion, homophobes almost always begin thus – “unnatural!” is their most common invective. Where do they find a nature to confirm them? They must know nothing of mud or marsh, creek or ocean – nothing even of their own wild hearts. To believe that homosexuality is unnatural, they need stay completely unfamiliar with the world outside – or within – where homosexuality is as common as dirt.

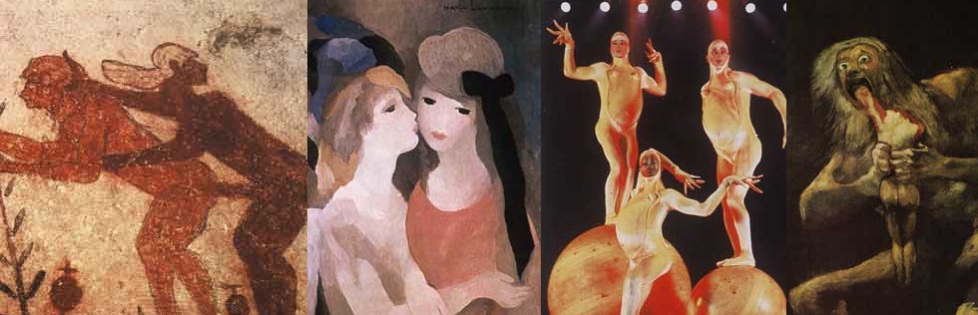

When homophobes call us “unnatural,” the nature they imagine is simple and desolate. It reflects only their own limited options. They think animals and even plants are always either male or female, and driven by a reproductive imperative. They dream that each species is bent on competition, engaged in a battle for survival that pits every life form against each other. They describe ants, swans, chimpanzees and flowers as if they have no moral life, no culture, and of course, no homosexuality.

In both Bottlenose Dolphins and Spinner Dolphins, animals of the same sex frequently engage in affectionate and sexual activities with one another. Sexual activity between female dolphins includes stimulation of the genital area by flukes or flippers, and a kind of “oral sex” in which one animal stimulates the other’s genitals with its beak. Sometimes female Spinner Dolphins swim together while one inserts her fin into the other’s genital slit.[iii]

Careful observation of nature yields another story. Birds do not come paired, male and female, as they do in bird books. They come in same-sex groups of three, five, and fifty. Bears and whales are among the many animals that form male and female same-sex pair bonds. They often raise adopted offspring. There is drag and performance in nature, as when a male hummingbird courts another male. He flies slowly back and forth, pivoting his body from side to side, flashing bright orange mouth lining and facial stripes.[iv] Cock-of-the-rock, a South American bird, performs ritual dancing ceremonies for males and females.[v] There is excess and abundance in the ripening of fruit and the impossible genesis of phytoplankton. There is mercy, as trees make air to breathe, and rains nourish the earth. Plants make potent medicines for animals and us. Birch trees act as nurse trees for newborn Douglas Firs, sharing sugars through their roots.[v]There is art and artifice in nature: beehive, bird’s nest, the figure-eights run by a female deer to arouse another doe. Sexes are not so opposite. There are many single-sex varieties of fish, lizards, snakes and salamanders. One all-female species of salamander has survived four million years.[vii]Certain species of fish change their gender through their life cycle, or when social circumstances demand it, restructuring both brains and genitalia from male to female and vice versa.[viii] Being queer, we are called to enter and partake of this world of nature, around and within us. We can see it clearly, in all its perversity and diversity. We can see and celebrate strangeness in the world and in ourselves.[ix] It is at least a beginning, from which we can work to forge an intimate and restorative relationship with the natural world.

Homosexual pair-bonds occur in both male and female Mallard Ducks. Male Mallard that have been raised ytogether frequently develop homoseual bonds of great strength and longevity. When large numbers of such birds are present, they often form their own groups, known as “clubs.”[x]

The homophobes have no beginning, no place from which to enter. To be and remain homophobic, they have to stay ignorant of complexity. They can never live with nature, singing its songs. Yet their homophobia can be seen to express a yearning for nature, along with a distance from it. It is a desperate, peculiar way to claim an affinity with the wild. They imagine that heterosexuality is natural through claiming homosexuality is not. Animals have nothing to say to them, but nevertheless, they claim a kinship. They imagine birds and bees are heterosexual, like them. They see the forest as scenery, or a resource. They will never be at home there. Still, they can feel their lives affirmed by its processes. They imagine each species engaged in competition, and bent on reproduction . . . so unlike the homosexuals. Homophobia imbues their awful, empty lives with magic naturalness. They assert a secure place for themselves and their values in the unfolding world, just by hating homosexuals.

On the other hand, enlightened democrats may claim that homosexuals are part of nature. Don’t blame gays and lesbians, they say. Queer folk are only victims of Mother Nature’s caprice. Fuelled with righteous certainty, they imagine the telling question: Why would anyone ever choose to be gay, when it occasions so much misery and loss? The notion that queer is a joy and a calling is anathema to the democrats. The democrats manage to hold the same dim view of nature as the homophobes, though giving grudging admittance to homosexuality. But it is hard to weave us into the culture of nature, without changing the colours and the pattern. Hence “the cause” is madly pursued. Is homosexuality an adaptation, a substitution, an aberration, a consequence? Is there a cure? Simply affirming that homosexuality exists throughout nature requires a reconceptualization of natural systems.[xi] It asks that we recognize multiplicity and mutability, magic and mystery.

The homophobe and the democrat want to live in a world ordered by scarcity (competition) and functionality (reproductive usefulness). We can begin to see it whole. Inside and outside, the world is wild. In all its intricate and unseen process, nature is alive with miracles and wonder.

[i] Nature Canada Autumn 2001 (27).

[ii] Hansard September 20, 1994.

[iii] Bruce Bagemihl, 1999.

[iv] Bruce Bagemihl, 1999.

[v] Catriona Sandilands, 1994.

[vi] Andrew Lewis, 1998, (3).

[vii] National Geographic, November 1992.

[viii] Jacques Cousteau, 1975, (62-5).

[ix] Catriona Sandilands, op. cit., 23, writes: “A politics that would celebrate ‘strangeness’ would place queer at the centre, rather than on the margins, of the discursive universe. It is not that we encounter ‘the stranger’ only when we visit ‘the wilderness,’ but that s/he/it inhabits even the most everyday of our actions. To treat the world as ‘strange’ is to open up the possibility of wonder, to speak also with the impenetrable space between the words in our language.”

[x] Bruce Bagemihl, 1999.

[xi] Bruce Bagemihl, 1999, explores ways in which acknowledging the widespread existence of animal homosexuality and non-reproductive sexualities invites a radical re-thinking of the natural world.