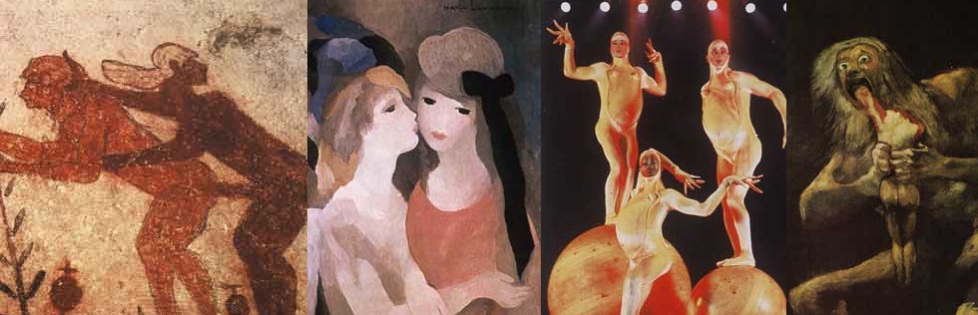

The Dream of the Three Magi, 12th Century. Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun.

The Dream of the Three Magi, 12th Century. Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun.

“My friend thinks I keep silence, who am only choked with letting it out so fast. Does he forget that new mines of secrecy are constantly opening up in me?”

– Henry David Thoreau[i]

In January 1933 Adolph Hitler became chancellor of Germany. Homosexual rights organizations were outlawed twenty-five days later. In May that year, the Nazis held a city-wide bookburning in Berlin. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Sciences was destroyed, along with his large collection of scholarly writings, case studies, and archival materials on homosexuality. Homosexuals were incarcerated in concentration camps, subjected to experiments by Nazi doctors, beaten, starved and gassed. Yet historical studies of the Third Reich rarely mention the persecution of homosexuals.

Emily Dickinson’s passionate letters to her sister-in-law were expurgated by her niece before they were published. All talk of kisses and ardent longings was excised. Michelangelo’s grandnephew changed the gendered pronouns of the artist’s sonnets to make it appear as if they were written to women instead of to boys and men. Alternative gender roles were widespread throughout North America, but anthropological records fail to mention it. King Rufus (England, 12th Century) was a flaming queen, but historians gloss over it. History, current events, social studies, art, science and sex education classes in schools fail to mention same-sex passions or homosexuality. The very existence of the GLBTQ population is burned up, cut out, covered up, ignored – with monstrous, deadly silence.

Silence = Death, as the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power put it, when for years no action was taken to research, combat and educate people on avoiding the virus killing gay men. If we fail to rupture the silence that surrounds us, we suffocate to death. So many queer folk do not survive their teenage years. They are bullied. They are murdered. They die of suicide, drugs, alcohol and HIV. They are choked to death by silence that denies them desire, agency, history and community. So many elders die in silence. Some fail to protect their “friends” with wills and legally-executed representation agreements. They would rather lose all security and betray their life partners than be named – even posthumously – homosexual.

Suffocating silence and “the deadly elasticity of heterosexist presumption,”[ii] as Eve Kofosky Sedgwick describes it, make “coming out” a continual task. Rupturing silence with an announcement of identity – with every new doctor, landlord, employee and P.T.A. meeting – is a process fraught with risk and anxiety. It takes enormous courage and has profound effects. It makes the air we breathe; it creates an environment that can sustain our lives.

We know in our bones the deadly effects of silence. Yet the silence that surrounds and suffocates queer identity also carries its gifts. Thomas Moore calls silence an aid to enchantment. He writes, “Silence is not an absence of sound but rather a shifting of attention toward sounds that speak to the soul . . . . Silence is a positive kind of hearing which requires turning off the knob that tunes in to the active, literal life and turning on the one that amplifies the movements of the soul.”[iii]

In silence, without names and precedents to direct our yearnings, each one of us has to divine identity and find our life’s direction by listening to the movement of our hearts. We are called to a soulful life through silence. Michel Foucault talks about the freedom silence makes possible, the multiple causes and meanings. He notes that in other cultures silence is “a specific form of experiencing a relationship with others.”[iv]

The silence that surrounds homosexuality makes simply “coming out” a transgression. Announcing our homosexuality, we reveal the invisible and say the unspeakable. Unannounced, queer slips back into the nether-world of secrecy and maybe-not. Queer people cannot exist without annunciation – continually repeated, judiciously withheld. Coming out always implicates those we come out to. Friends and family often feel themselves contaminated with homosexuality and concerned with defending themselves against it. Alternately, our identity can function as an opening for those who hear us, a crack in the obdurate wall of heterosexist conformity. Sometimes they can slip through to join us in a starry sky of passion and possibility.

Our mouths are sex organs when they speak the forbidden language of difference. Coming out is an erotic act. Modern life bifurcates people into visible surface and inner self.[v] Historical, cultural and economic forces wrench individuals free from predictable lifeways and social contexts where they are “known.” Superficial social interactions demand more and more energy, while the “inner essence” that is each person’s history, fantasy, dream and desire is constituted as a territory withheld from social life. The self is secret, and its deepest secrets are sexual secrets – libidinal drives and guilty narratives of sexual wounds and woundings. There is a yearning to be touched, seen, permitted and forgiven, and the defended territory of the “inner self” is constitutionally incapable of satisfying that yearning – at least in the superficial interactions of everyday life.

Coming out refers to this dark, secret, silent place within; it calls the “inner essence” into an act of speech. At the moment of annunciation, we give our selves away, surrendering the paranoid territory of a self that is constituted by withholding. Instead of confining our sexuality to secret sexual acts, in coming out we claim a public sexual identity. The secret is out; we make our selves the hot and slippery subject of public discourse. The air is charged with libidinal energy when we bring our selves out in social intercourse.

When we “come out,” our richly productive inwardness is sublimated to social purposes. Annunciation is an act of self-disclosure that is simultaneously an act of service – a way to align the self with, and to act in the service of, the queer community. The self conceived in this disclosure is not individual. Transfigured by annunciation, it cannot stay self-identical. Dag Hammarskjöld, Swedish economist, Secretary General of the United Nations from 1953 until his death in 1957, international peacemaker, Nobel Prize laureate, dedicated public servant, and homosexual, writes, “. . .I can realize my individuality by becoming a bridge for others, a stone in the temple of righteousness.”[vi] Just so, coming out is a way of realizing individuality by becoming a stone, a bridge, a representative specimen.

Hammarskjöld writes of his calling, “To preserve the silence within – amid all the noise. To remain open and quiet, a moist humus in the fertile darkness where the rain falls and the grain ripens – no matter how many tramp across the parade-ground in whirling dust under an arid sky.”[vii] If we live, the silence surrounding gay and lesbian existence can open a fertile space inside the soul. Silence can be a meditative practice and a spiritual discipline. It is a way to find the inmost images, and become nourished by the deepest wisdom. The richest veins of creativity and love can only be tapped in silence.

Queer identity is always new. Hammarskjöld writes of holding out “the chalice of our being to receive, to carry and give back. It must be held out empty – for the past must only be reflected in its polish, its shape, its capacity.”[viii] The past does not limit us. Language does not structure each startling movement of the heart. We are secret, silent, and in Hammarskjöld’s sense, empty. We have to invent ourselves and each other. We live always new like a river: running clean, making tracks as we go. And the thick mud of the riverbed is dark and rich with forever. We have no beginning. We have no end.

Affirming and creating ourselves as queer persons with each annunciation, we can say with Hammarskjöld, “each day the first day: each day a life.”

[i] Henry David Thoreau, 1841 Journal, quoted in Katz, 1976, (210).

[ii] Eve Kosofky Sedgwick, 1990, (68).

[iii] Thomas Moore, 1996, (104).

[iv] Stephen Riggins interview 1983.

[v] As Henning Bech, 1997, points out. He writes: “At the same time a surface is formed, an inner, a depth, an essence develops – a self. This is partly a kind of residuum of what was before and what otherwise is and cannot get absorbed in the surface: being Fred Bloggs, siring his children, boozing away his pay, and so on. . . . What we have, then, is a person who has fallen into two parts: an inner self on the one hand, and a surface on the other.” (164-5).

[vi] Dag Hammarskjöld, 1964, ( 62).

[vii] Dag Hammarskjöld, 1964, (83).

[viii] ibid., (127). The quote in the following paragraph is also from page 127.