Two Hearts that Beat as One, Life in the British Armed Forces, East Kent Mounted Rifles, 1921

Two Hearts that Beat as One, Life in the British Armed Forces, East Kent Mounted Rifles, 1921

“This dread of homosexuality makes, of course, no sense if homosexuality really could be limited to those few percent that most population surveys suggest. Homosexuality can only be a global threat if globally present.”

– Henning Bech

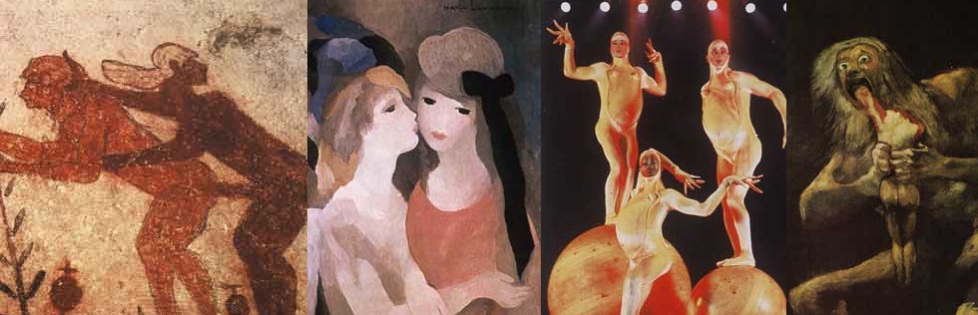

In Elizabethan England, male friendship was valorized as the highest possible human relation. Male friendships were affectionate, erotic, and most certainly involved sex. Sodomy, on the other hand, was demonized, punishable by death. Allan Bray notes that the codes describing friendship and sodomy were virtually identical, but the two were rigorously and anxiously distinguished.[ii] Friendship did not cross class difference. Sodomy involved the transgression of social hierarchies. And according to the Elizabethan world view, social hierarchies were simultaneously cosmic hierarchies. Sex and even love between men of different ages and classes had earth-shattering implications. Sodomy admitted a terrifying disorder to the embattled chain of being.

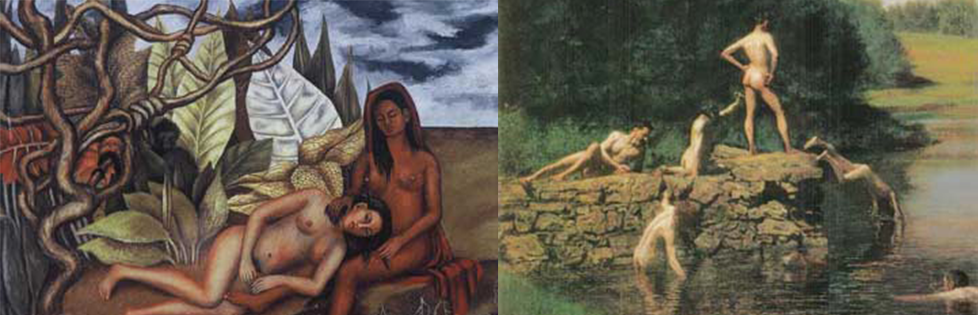

Love relationships, including erotic exchanges, were encouraged in medieval nunneries. But if a woman was found to have penetrated another with an object, she could be put to death.[iii] Lillian Faderman writes of love between women from the Renaissance to the present, noting that society appeared to condone romantic friendships and even lesbian sex. But when women wore male dress and usurped masculine privileges, they were persecuted and sometimes executed. Same-sex passions were permissible – but only within limits defined by acquiescence to class and gender hierarchies.

Passionate friendship remained a possibility and even an expectation until homosexuality came on the scene. From the mid-19th century, homosexuality was produced as a concept by social and economic conditions, sexologists, anti-feminists, psychoanalysts, and people who wanted to craft a life around their same-sex attachments. Sex between people of the same gender took on new meanings and consequences with the advent of homosexuality. In prior centuries, the consequences of engaging in acts of sodomy could include exile, imprisonment, torture, castration, and death, but not psychological treatment, scientific scrutiny, and self-acceptance. Delight in flesh within a passionate friendship would not likely demand the break-up of a marriage, the restructuring of identity, and coming out of the closet.

Marie Laurencin, The Kiss, 1927

When there is a minority called homosexual, friendships lose their fluidity. Relationships that previously could include interludes of sex in a lifetime of loving become possessed of a need to disavow – or claim – the possibility of same-sex eroticism. In 1852 Emily Dickinson could write unselfconsciously to her beloved sister-in-law, “Susie, will you indeed come home next Saturday, and be my own again, and kiss me as you used to? . . . . I hope for you so much and feel so eager for you, feel that I cannot wait, feel that now I must have you – that the expectation once more to see your face again, makes me feel hot and feverish, and my heart beats so fast . . . .”[iv] Dickinson’s niece deleted all of the sexual implications from the letters published in the 1920’s, aware that love between women was condemned as perversion. The identification and stigmatization of same-sex eroticism as homosexuality, and the corresponding effort to display the absence of sex in same-sex relationships, did not happen all at once and overnight. Even today some passionate friends hang on doggedly to their “innocence,” pursuing a range of romantic and sensual expressions without either claiming or repudiating homosexuality.

In a study of the sex life of American white, middle-class women undertaken from 1918 through the 1920’s, Katherine Davis found that 50 percent of single women had intense emotional relations with women and 50 percent of these relationships were decidedly sexual. Among married women, 30 percent had fallen in love with other women, and half of these relationships were sexual.[v] Alfred Kinsey, in his research into Sexual Behavior in the Human Male in the 1930’s and 1940’s, found that 37 percent of men surveyed reported at least one homosexual contact to the point of orgasm. Another ten percent of males were more or less exclusively homosexual for at least three years. He concluded that 50 percent of men had some kind of homosexual experience. Subsequent sex researchers have failed to reproduce these statistics. A 2001 survey of Canadians found that only 2.6% have had a sexual relationship with a person of the same sex (and that no residents of Alberta were among them!). In the U.S.A. a 1992 survey found that only 7.1 percent of men and 3.8 percent of women reported some type of sexual contact with a same-sex partner since puberty.[vi] It seems that the incidence of same-sex eroticism has significantly declined in the years since Davis and Kinsey did their research. As homosexuality becomes increasingly visible in the culture, it is increasingly absent from same-sex relationships.

When same-sex passions and attachments no longer take place in an unscrutinized, unstigmatized field, the possibility of sex between men and between women declines. Freud remarked in 1915 that “all human beings are capable of making a homosexual object choice and have in fact made one in their unconscious.”[vii] The possibility and promise of same-sex eroticism is everywhere visible, in sports, movies, advertising, religious imagery, and the largely homosocial environments of work and leisure. Yet these same spaces are governed by what Henning Bech describes as the “imperative of repudiating homosexuality.”[viii] The possibility of same-sex eroticism is conjured, only to be disavowed. Same-sex sexuality is denied, camouflaged, or blatantly expressed, only to be clearly separated (shown as belonging only to the homosexuals).

Gender-marked and homosocial spaces – locker room, girls’ school, sports team, kitchen, army barracks – could, and once did, radiate with erotic energy. These spaces are increasingly marked by what Bech calls “absent homosexuality.” Homosexuality is conjured and repudiated, through queer-baiting, posturing about heterosexual conquests, silence about the beauty of each others’ bodies. Absent homosexuality affects all friendships. Intimate same-sex relationships must continually repudiate homosexuality, or claim it, or be avoided altogether. Homosexualized, while they are defended against and deprived of homosexuality, intergenerational relationships are seized and destroyed by the awful omnipresence of absent homosexuality. Absent homosexuality becomes an emptiness at the heart of all human relationships.

A. Castaigne, Bull Dance, 19th C engraving

Bech describes absent homosexuality as “a major organizing power of modern societies, on a par with other great agents such as capital and bureaucracy.”[ix] Absent homosexuality continually manages the possibility of same-sex eroticism, confining it to ghettoized enclaves and pathologized persons. All same-sex passions are stigmatized. Unlike passionate friends of past centuries, every homosexual constitutes a social threat.

The rich history of same-sex passion notwithstanding, previous eras afforded no space for being homosexual. Passionate friendships involved sexual acts, not whole identities. When sex between men and between women can happen without being identified as queer, same-sex passions can actually facilitate the functioning of existing class and gender hierarchies. Homosexuality is different from this; it carries within it the radical revisioning of legal, social and institutional limits. Michael Foucault describes it thus: “To be gay is to be in a state of becoming. . . . To be gay signifies that [the sexual choices one makes] diffuse themselves across the entire life; it is also a certain manner of refusing the modes of life offered; it is to make a sexual choice into the impetus for a change of existence.” [x]

The anxious, desperate, soul-destroying disavowal of homosexuality that confronts us everywhere paradoxically affirms or even creates a radical space for homosexual existence. The fear of homosexuality pervading 21st-century Western culture establishes being queer as a lived otherness with mythic dimensions. Absent homosexuality locates the possibility of homosexuality outside of the homosexuals, effectively queering every human relationship. In the form of disavowal and the presence of absence, homosexuality is everywhere. Queer is a state of becoming that we are still calling, as it calls us, into life.

[i] Henning Bech, 1997, (62). Emphasis original.

[ii] Alan Bray, 1990.

[iii] Karin Lofthus Carrington in Hopke et. al., 1993.

[iv] The Letters of Emily Dickinson, eds. Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Wars (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958), Letter 96, quoted in Lillian Faderman, 1981, (176).

[v] Margot Francis, 1996, (36-7).

[vi] Edward O. Lauman, John H. Gagnon, Robert T. Michael and Stuart Michaels, The Social Organization of Sexuality: Sexual Practices in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), reported in Francis Mark Mondimore, 1996, (89).

[vii] Sigmund Freud, Standard Edition Vol.7, (145-146 n.).

[viii] Henning Bech, op.cit., (55).

[ix] ibid., (82).

[x] quoted by David Halperin, 1995, (77-78).