by Caffyn Kelley

Beginning

Between 1983 and 2002, more than sixty women vanished from the mean streets of Vancouver’s downtown eastside in the context of a vast silence and inattention from the public and police. Now that teeth and toes have been sifted from pig shit on a Port Coquitlam farm, the public sphere resounds with representations. Journalists crowd the trial of the accused serial killer. There is outrage, fascination, a hunger for detail. Yet women in the downtown eastside of Vancouver today still live with violence and urgent danger. What kind of monument, what form of remembering, might actually contest this space?

Some fifteen years ago, a group of feminists worked hard to create a lasting monument dedicated to “all the women murdered by men” in the downtown eastside of Vancouver. The monument was inspired not by the native women, sex-trade workers and drug addicts murdered and missing in this dangerous neighbourhood, but by the slaughter of fourteen female engineering students from 4000 miles away. Elsewhere I have written on the construction of race, class and whiteness implied by the “Women’s Monument” (Kelley, 1995). A recent article by neighbourhood resident Taylor (2006) affirms that this continues to insult the women of the downtown eastside. Without denying the achievements of the project, I believe that its failures invite us to begin again.

The “Women’s Monument” inserts the presence of murdered women into a terrain where women are silenced and endangered. In so doing, it excites controversy; it challenges the prevailing organization of space. Yet perhaps its claim to space is not radical enough; its dream is too small. The monument seeks to empower “women” within the parameters of a culture that sustains power through the powerlessness of excluded others. It fails to embrace the challenge of difference, or to address the operation of dominance and entitlement in a system of unequal development that distinguishes women from one another. If we see sexism, racism and relative worth as central features in the design and construction of space, we might choose new beginnings. Rather than seeking to value women inside a system that generates value through unequal development, we might instead use women’s experience of exclusion to suggest new cultural strategies. We need a monument that will initiate new relationships with one another, with value, and with the natural world.

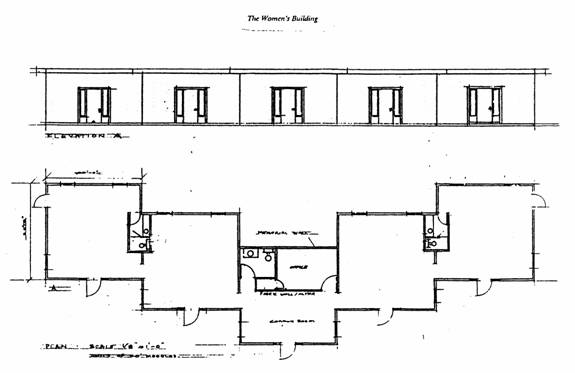

My own 1993 design for a “Women’s Monument” was inspired by a question posed by the project organizers. In an invitation to designers, they wrote: “Monuments have traditionally been built to remember figures and events in history that men have considered important. How would a women’s monument be different?” This question helped me to move my work from the sterile realm of art. In this realm, women have been excluded and their work denigrated. But this exclusion has never prevented women from doing creative work: artful paintings and sculpture, yes, and also quilts, food, clothing, gardens…. In women’s approaches, art can be enhanced and not diminished by its usefulness. Creative work can be an opportunity to establish resources, build bridges, and design points of connection.

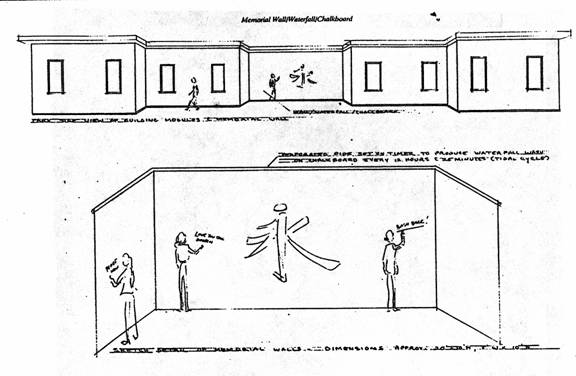

My design for a “Women’s Monument” in the downtown eastside suggested a “Women’s Building” that could serve as shelter and safety for the women of the neighbourhood. While incorporating art and landscape in a deep poetry of the psyche, the design also provided a space for community and made bridges between communities. I envisioned the monument as a place to imagine new forms of power, strengthened by diversity and structured by openness. I suggested excavating the buried landscape, restoring habitat, and allowing wild nature to inform the work. Designing the “Women’s Monument” as building, pond, garden, playground and interactive public memorial, I understood that a monument need not simply be art – a static object of value – but instead, could function as an open system that accepts change and encourages repeated, intimate participation.

The Buried Landscape: Queering “Woman”

Butler (1990) writes “Gender is not to culture as sex is to nature; gender is also the discursive/cultural means by which ‘sexed nature’ or a ‘natural sex’ is produced and established as ‘prediscursive,’ prior to culture, a politically neutral surface on which culture acts” (p. 7). The traditional monument takes up residence in this domain, promoting masculine power and the joys of reproductive heterosexuality with an erect phallus straining towards the sky. A monument to commemorate women and feminized men who are victims of violence might invert these meanings. It might attend to the connections between wild, woman and queer that lie buried in culture of nature we inherit. What kind of monument would nourish complexity and allow wildness to flourish? My design for victims of homophobic violence in Winnipeg (1995) included a tallgrass prairie garden and a daylighted creek. It used shapes, horizontal movement, words and restored habitat to make space in which the suppression of diversity is posed as a profound and dangerous cultural pattern.

Bordieu (1992) points out that when we say culture/nature, we are not so far from saying man/woman, subject/object, human/inhuman, active/passive, controllable/ uncontrollable…. Bordieu complains that these oppositions “think in our place” (p. 40). They “function as the most absolute system of censure, since they are … the things which structure what is thought, and therefore they are themselves very difficult to think” (p. 39). We march on the Mobius strip comprised of these opposites, forever traveling between seeming reversals. How might we empower something other than opposite? Our present ecological crisis informs us with some urgency that we need to find a way out. We cannot simply lay claim to men’s value and power, without challenging the whole system in which woman’s opposition is posed. In a world where “resource destruction… has been positively valued as a productive [masculine] activity, while more passive, less intrusive participation in life’s regenerative processes has been denigrated as feminine and unproductive” (Vandana Shiva, n.d.) we need to build space to recall the vast diversity of natural communities. We need to ask: “What protects your power?” “What guarantees your difference?” “What form of remembering would not remember this?”

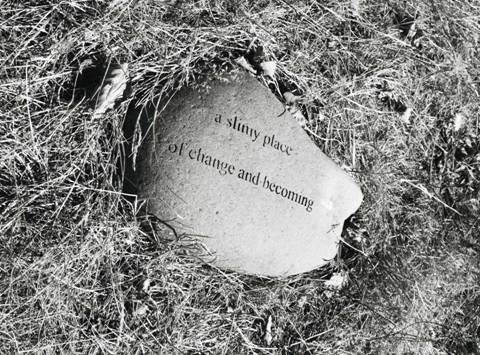

In a Vancouver park I actually had the opportunity to construct a small monument in the land. It lasted about six weeks before it was removed by the Park Board to make way for a baseball outfield. Water Dream / Water Memory (2002) was a memorial to a buried ecosystem. I worked with a community to build a 400-foot long dry creekbed following the path of a buried stream. The environmental sculpture incorporated river rocks, riparian plants, and rocks engraved with a poem about water. The concept involved creating a tiny complex piece of nature to serve as habitat. It echoed an intricate, unseen and refused (queer) nature; it explored connections between blood, tears, constrained complexity, and a buried stream. Water Dream / Water Memory invited visitors to embrace the intersection between self and world. Listening to elements, we might attend to their flow through our own bodies, finding there an openness to new (or old) forms of agency within the tangle of self and other.

Writing on the earth, I conjure an archetype: woman / mother /earth. Carl Jung (1959) calls this archetype “the mysterious root of all growth and change; the love that means homecoming, shelter, and the long silence from which everything begins and in which everything ends.” Here is the wild order of life and death, the deepest mystery. Jung continues, “Intimately known and strange like Nature, lovingly tender and yet cruel like fate, joyous and untiring giver of life – mater dolorosa and mute implacable portal that closes upon the dead.” Excavating the archetype, I risk the stereotype that would tie woman and nature in a pliant unity, obscuring the social relationships that construct these concepts in subordinate relation to man and culture. And yet, as I have explored in detail elsewhere (Kelley, 2003), there is an electric space between empty stereotypes that keep us locked in trivialities, and powerful archetypes that link us with myth and history. Jung (1949) writes, “Not for a moment dare we succumb to the illusion that an archetype can finally be explained and disposed of. . . . The most we can do is to dream the myth onwards. . . .”

Water Dream/Water Memory:images from the built project (now destroyed)

The City and the Suburbs

How, and where, might we build an appropriate monument to the murdered women from the downtown eastside of Vancouver who died on a pig farm in Port Coquitlam? Alongside acres of recently-built, picture-perfect suburban homes, 953 Dominion Avenue is a 10-acre wasteland, completely denuded by forensic teams combing through mud and shit in search of bone fragments big enough to yield the murdered women’s DNA.

The city and its suburbs is the landscape in which the scene is set for the murder of women. Here land expropriated without compensation from native people is the basis of wealth in a system of land tenure from which native people are completely excluded. Real estate speculation proceeds at a hectic pace, generating both wealth and poverty in a system of unequal development. In the early 1960’s the Picton family purchased swampland just west of the Pitt River when fewer than 10,000 people lived there. Today Port Coquitlam is one of Canada’s fastest-growing suburbs and a paragon of urban sprawl. Most of the more than 50,000 residents make the long commute into Vancouver, driving 45 miles each day. The Pictons made a fortune selling the wetlands for development; two land sales in the 1990’s netted 3.5 million dollars.

Twenty-two miles west the downtown eastside of Vancouver sits on another buried wetland. Thanks to police crackdowns on the relatively safe practice of hotel prostitution and the successful efforts of outraged citizen’s groups to evict the sex trade from other, less disempowered neighbourhoods, prostitutes share dark alleys with drug dealers and turn tricks in cars. “From 1985 to 1989, 22 prostitutes were murdered in Vancouver. From 1990 to 1994, there were 24 murders. Since then, another 50 or 60 women have likely been murdered,” writes Gardner (2002). The downtown eastside is an enclave of poverty and danger at the nervous edge of an otherwise thriving city. (Vancouver is “the world’s most desirable place to live,” according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s liveability survey, which looked at conditions in 127 cities. See McKenna, 2005).

Every existing physical space is simultaneously a cultural space; the relationships between spaces denote a cultural practice. Between the liveable city and the alluring suburbs, the downtown eastside is a cautionary tale for women. Taylor (2006) describes the women of the neighbourhood as “raising shit and resisting.” These women don’t matter to feminists, the media, the public and the police because of “not finishing university or high school, not marrying an upwardly mobile (well-to-do) guy, not being an anonymous wage-slave, having and losing independence and using/abusing one or more substances, leaving an abusive relationship or an abusive home life, getting caught up in the lifestyle of one’s chosen or just found micro-community and acquiring the monikers addict or junkie or hooker or mule or fluff or mental case… and the categorization in this illusory hierarchy sticks like tar.” In contrast, the suburban women of Port Coquitlam are – however provisionally – women who matter. Taylor reflects on the outcry that ensues if even one obedient middle-class white woman is murdered.

Creating a memorial for the other(ed) women whose body parts were excavated from the suburban mud, we can contest this geography. Whose interests are served by unlinking the practice of prostitutes frequented by suburban men from the privileges and precariousness of suburban women? A monument on Dominion Street in Port Coquitlam could include designs for housing, transportation, drug rehabilitation, a bordello, and a community garden: spaces for conversation, designs to provoke engagement, and economic strategies for the empowerment of women from diverse backgrounds and locations. Rather than inviting specific responses, a design might make room for a vast array of personal responses, within a territory that renders “public space” a living possibility.

Dreaming

What form of attention, culture, or memorial might actually address the conditions that engender the murder of women? A fitting monument to the missing and murdered women of Vancouver’s downtown eastside will acknowledge the depth of grievous loss; it will begin the work of atonement and repair. It will speak to the multiple ways in which specific oppressions and entitlements shape our lives, our culture, and the land beneath our feet. It will honour our kinship with all life, without disallowing the radically different ways we are endangered because of class, race and sexuality. It will contest the system of suburb and city, and create a public sphere. It will change what – and who – matters.

I dream of making such monuments – spaces that may be described as utopian, impossible. But if we forget what is not possible, the unthought aches, like phantom pain in amputated limbs. It may be more fitting that the monuments I design do not (yet) exist in specific places. I imagine an invisible, viral replication of ideas that infect, and finally overwhelm, the body politic that makes such monuments necessary.

References:

Armstrong, J. (May 25, 2002). O brothers, what art thou? The Globe and Mail.http://www.missingpeople.net/o_brothers,_what_art_thou-may_25,_2002.htm

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, NY: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1992). Thinking about limits. Theory, Culture and Society, Vol. 9, pp. 37-49.

Gardner, D. (June 15, 2002). Courting death: (Part 2) The law has hounded hookers out of safe areas and into dark alleys, making them easy prey for murderers. The Ottawa Citizen. http://www.missingpeople.net/courting_death_part_2-the_law_has_hounded_hookers-june_15,_2002.htm

Kelley, C. (1995). “Creating Memory: Contesting History: Inside the Monstrous Fact of Whiteness,” Matriart, Vol. 5 #3. The publication omitted a crucial section of the essay which has now been restored (2006).http://www.saltspring.com/hideaway/Caffyn/Papers/Creating-Memory.pdf

Kelley, C. (2003). Orientation: Mapping Queer Meanings. www.queermap.com

Jung, C. G. and C. Kerényi. (1949). Essays on a Science of Mythology: The Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. trans. R.F.C. Hull. Bollingen Series XXII. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1959). (1993). ed. Violet Staub de Laszlo. The Basic Writings of C. G. Jung. New York: Modern Library.

McKenna, J. (October 3, 2005) “Vancouver tops liveability ranking according to a new survey by the Economist Intelligence Unit” Economist Intelligence Unit, The Economist. http://store.eiu.com/index.asp?layout=pr_story&press_id=660001866&ref=pr_list

Matas, R. (September 27, 2000). Transformed by urban sprawl, Vancouver says its plan is working. The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/series/sprawl/0927_a.html

Shiva, V. (n.d.) Ecological Recovery and the feminine principle. Retrieved online Nov. 2006 athttp://www.pcdf.org/1993/50shiva.htm

Statistics Canada. (October 1, 2003). Homicides. The Daily.http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/031001/d031001a.htm

Taylor, Paulr. The World is Listening. Carnegie Newsletter, February 15, 2006. Retrieved online December 14, 2006 athttp://carnegie.vcn.bc.ca/index.pl/february_1506_page01